“The Impact of Modern Life on Mental Illness”

Awareness and acceptance of mental health issues in the general population has increased in the last decade. In fact, one might consider asking whether there is an increase in awareness, or whether there is an actual increase in people presenting with mental health issues, than say, 50 years ago.

I was browsing an article on this topic, about a scientific study that showed an increase in mental health issues in teenagers compared to their Gen X counterparts. In the comments, someone mentioned a recently published book that explores this topic, by a psychiatrist. This is a summary of that book: Frontal Fatigue by Dr. Mark Rego.

Anecdotally, I have long felt that keeping guard rails on my own internet usage helped me a lot. I have noticed that the more unfocused browsing and scrolling that I engage in, the more likely I am to feel anxious, listless and isolated. I had read a lot in the nosurf/digital minimalism communities about people experiencing ADHD-like symptoms and issues with focus and concentration that disappeared or were significantly lessened by reducing their technology usage. I was curious to see whether Dr. Rego had noticed the same in his professional practice, and if he could offer some explanation as to why this was happening.

This book offers a holistic and in-depth treatment of the topic. At times, some of the more scientific material was a little over my head, but I did appreciate the author’s depth of experience and his willingness to share his expertise on this topic. It is definitely not an easy read, but I found it a very valuable and interesting perspective that is often missing in discussions on this topic.

Part I: The Mental Illness Epidemic

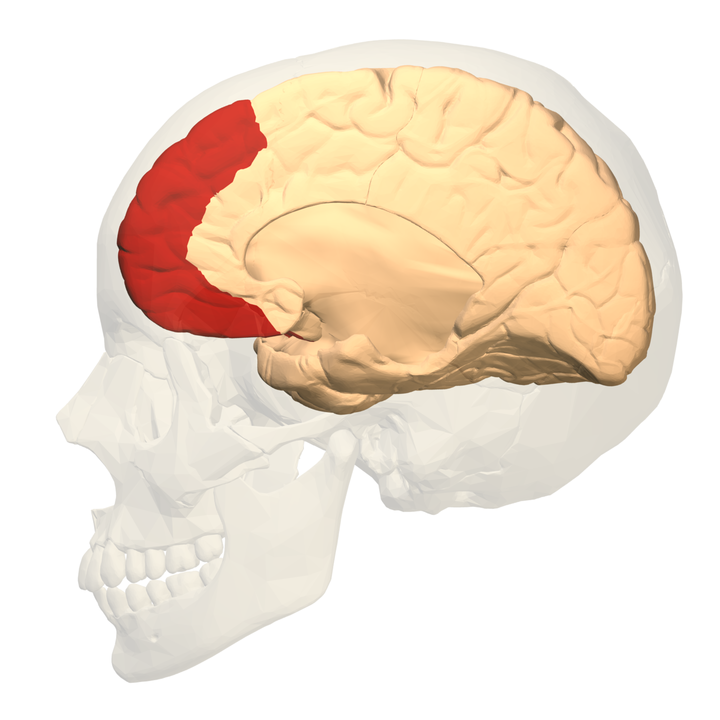

Why is it that mental illness is more severe and more pervasive in our society than at any other time in human history? This is the question that Dr. Rego sets out to answer. His theory, and the central theme that will be discussed throughout the book, is that modern life (and particularly its reliance on technology) creates a certain kind of mental stress that our prefrontal cortex (PFC) must handle. Unfortunately, the PFC does not function well under stress, and this subsequent loss of function can activate some mental illnesses that we might be susceptible to. However, not all mental illnesses are related to PFC stress, and there are some (autism spectrum conditions, intellectual disabilities, dementia, personality disorders, and PTSD) that are excluded from discussion in this book, either because they are not increasing significantly in frequency, or because they have been shown to have different causes.

The remainder of this part discusses the kinds of mental illnesses that are increasing in both frequency and severity, and that Dr. Rego believes have some link to the stresses of modern life. Anxiety, depression, and burnout are some that I expected to see, and I was interested to read a psychiatrist’s description of what patients presenting with these illnesses tend to say, as well as the effects the illness has on every aspect of their lives. Some disorders that I was not expecting to see here were bipolar disorder, ADHD, and schizophrenia.

One thing that is mentioned towards the end of this part is the correlation between some of these disorders and urbanization and immigration. That is, people who have moved to a more urbanized environment or who are immigrants also show increased levels of these mental disorders. The conclusion is that even though we are living in a time of unsurpassed wealth, security, and technology to help us with menial tasks, we are less attentive, more depressed, more anxious and generally less psychologically well than older generations. The more severe mental illnesses present themselves earlier, and the road to recovery is much rockier than it has been previously. Now that these questions have been set up, the remainder of the book sets out to answer them.

Part II: Modern Life

What are the specific aspects of modern life that could be responsible for our mental stress?

One answer is technology. Since the 1950s, state-of-the-art technology has been less focused on physical tasks such as transporting heavy loads, and more for transmitting information. There is an entirely new family of technology in the form of smartphones, tablets, laptops etc. Improvements in technology have even made it so that what is happening in the physical world is less of a concern – for example, after COVID-19, many people no longer need to be co-located in order to work together effectively. Technology also has an effect on our culture. Ideas about what to value, our identity, dress, behaviour, how we should relax, are all influenced and shaped by the technology that we have available to us.

In most technology-centred societies, one can function very well while paying little or no attention to what is happening in the physical world around them. This brings new freedoms and new choices – people have access to information that they did not have in the past, and therefore new choices that they did not have to reason about before.

As well as that, just by using technology, we are faced with decisions that are complex and abstract. We also have to do this with (for many of us) no knowledge about the inner workings of the devices that we are relying on. This adds complexity to our lives that tends to compound – we do not understand the technology that enables a smartphone the more that we use it, because how it works is obscured from us. We have gained much more ease and efficiency, but at the cost of imposing more decisions and more complexity upon the prefrontal cortex.

Part III: Why Are We Sicker?

There are multiple theories and explanations for mental health changes in modern societies – falling into the categories of biological, psychological, and social. However they all follow from one common observation – that we have drifted significantly from our evolutionary origins. As hunter-gatherers, humans ate simply, exercised a lot, and were rarely alone. Humans evolved into this life, and became physically and psychologically suited to it.

Biological theories for the rise of mental illness include diet, lack of physical activity, light and sleep. While there is a link between obesity and depression, other groups of patients do not tend to be overweight. There is also an association between increased physical activity and reduced depression and anxiety. Lack of sleep impairs mood and concentration, and is a strong predictor of developing depression. Lack of exposure to natural light alters our circadian rhythms, and leads to vitamin D deficiency.

Our environments are more confusing these days, due to the amount of technology we are reliant on that we don’t understand. We are also lonely and isolated. We often spend hours out of each day interacting with our smartphones and computers. Time spent using a device is time spent absent from our surroundings.

There are also societal factors such as people’s circle of trust becoming smaller. It is less common now for people to know their neighbours, or to have people in their community that they regularly see, even if they don’t know them well. These informal relationships serve to diffuse some mental tension for us – we expect that the people we see frequently would help us if we were in trouble. At present, much of our casual interaction with other people has been replaced with interacting with a device. While these can sometimes be useful (I found the recommendation to read this book through a comment section), it is not the same as engaging with a nearby person, and does not provide a sense of trust and acknowledgement in our local communities.

Part IV: The Prefrontal Cortex – The Jewel in the Crown

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays an important role in multiple types of function, including senses, motor function, speech and many other complex tasks. However, it is not the source of any of these functions. It takes data from many brain regions and assembles them into forms that we can use consciously. It also has a role in how what we process through our senses affects us emotionally.

The PFC handles executive function, our ability to form symbolic representation from data, and the ability to switch and reform these symbols. These three functions are the building blocks for sophisticated thought and decision-making. The PFC also constrains the following types of behaviour – distractibility, perseveration (the repetition of a word, phrase, or simple gesture when there is no need for it), and disinhibition (impulsive decisions without regard for consequences). These behaviours are often seen in people with PFC dysfunction.

The PFC also has some special functions that may be somewhat unexpected. It plays a significant role in our ability to tolerate and interact with novelty, uncertainty and ambiguity in the environment. It also influences our capacity to sense significance, context and ambiguity in social situations, as well as our abilities to switch perspectives and see things from another point of view.

Keeping all this in mind, how does our PFC react when it is under stress? We often talk about the brain as if it is a muscle – it gets tired, it needs a rest. It turns out that this is a useful metaphor – when the PFC function is isolated in scientific experiments, it has been shown that the PFC does get fatigued. This is unusual as other brain areas do not behave in this way. When stress is increased beyond a certain point, we lose PFC function quite rapidly. It can be more difficult to focus and concentrate, and we can lose the ability to read the emotional dimension of what is happening around us. We can experience problems with our working memory, forgetfulness, and disorganisation.

Part V: Frontal Fatigue – Our Weary PFCs and Mental Illness

Modern life places demands of complexity, abstraction, and reformatting on all of us. This kind of stress is new to humanity, and can only be handled by the prefrontal cortex. However, the PFC is not a stress response organ, and will deteriorate when it is fatigued. Modern neuroscience has shown that the PFC is involved in almost all forms of known mental illness, and it is now known that stress to the PFC does produce mental illness. Technology provides solutions to problems, unfortunately these solutions tend to stress our PFCs. There is much less emphasis on ways that we are inherently evolved to cope with stress i.e. interpersonal support, traditions, nature.

Dr. Rego sees this as a broader societal trend that cannot be reduced to smartphone usage. Our societies have become much more complex, and those who already have PFC dysfunction will have difficulties with this. Covid-19 is a good example of this – young people were isolated and made dependent on technology when they should have been broadening their social circles and skills. The result is that many of them have suffered a decline in their mental health. However, frontal fatigue affects everyone – our work is more complex, societal roles are less defined, and there are huge numbers of choices to make about what direction to take and how to spend one’s time.

Part VI: Coping in a PFC-Centred World

Dr. Rego sets out some practical advice to help your PFC. He believes that the trend of frontal fatigue will continue to worsen over time, as there does not seem to be much change forthcoming. First, we should identify whether our PFC is under stress. Some common symptoms of this include lack of focus, trouble finding words, the feeling of having to mentally strain to do something engaging (like reading a technical book). Difficulty multitasking and irritability are also common signs. If one is experiencing these issues, there are two families of strategies for tackling them, either externally or internally.

The external strategies are to interact with the world via our hands, senses (i.e. spending time with art or things we are curious about), and activities that are social and can be done with other people.

The internal strategies are to do with mental activities that do not directly focus the PFC, although they do engage it in certain ways. By doing this, we can improve how the PFC operates. One is to find a way to quiet the mind, without vegging out like when we watch TV. Some examples of this are quiet activities like painting, breathing exercises or meditation. Reading deeply is also a good practice – he recommends finding something that takes at least a few 30 minute sittings to complete.

Conclusion

This book definitely helped me gain a deeper understanding of how technology can affect our brains. I appreciated the more holistic view of technology in our society, and how it is more than just smartphones and online entertainment. The last two sections I found particularly useful – the tools he presents to identify whether you are experiencing frontal fatigue and how to mitigate this seem very valuable. It allows me to understand what activities I am engaging in that are unhelpful, and how to structure my life in a way that gives my PFC a chance to rest.

I would recommend this book to anyone who feels that technology overuse impacts them negatively in terms of their mood, focus, and behaviour. It is detailed, and quite scientific in parts, but it is worth putting the effort in to engage with the ideas if you are interested in understanding how to tailor your technology use to your own life.