Imagine a day full of intentional activities. Whether at work or play, you are following your intentions and feel present, focused and undistracted in each moment. In the work environment, this is sometimes known as a state of flow or deep work. At home, you might call it mindfulness. It was a good day, you lived well, got stuff done, had some dedicated relaxation time, and go to bed satisfied.

Now imagine a day where you cannot focus. Your mind is wandering. Worries keep popping up in your thoughts, and in this state of anxiety you seem unable to enjoy the tasks you are working on or to make any significant progress. You comfort yourself with snacks or consume social media and snippets of news: somehow this makes the day bearable, but you know something is not quite right.

When we cannot focus, we are less happy. You probably know this, intuitively, from your personal experience, if you’ve had days like the two above. It is also backed up by research. In the 2010 paper, A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind, participants were prompted throughout the day by an app, to answer questions about what they are doing, whether they are thinking about the activity they are doing, and how happy they feel at that moment. The results showed that people who were thinking about something other than what they were doing tended to be less happy.

What’s more, the study also showed that a wandering mind is extremely common: people reported that they were not thinking about their current activity almost half the time. If we are perhaps spending half our lives not present to our current activity, less productive and less happy, then it seems wise to do something about this.

A wandering mind is a reactive mind

If you are not focused, this is because you are reacting to distractions (also known as interruptions or stimuli). A distraction is anything that you react to (and in particular here, we are concerned about stimuli which are not related to your current task or activity).

It might not feel like you are reacting to distractions, but if you really watch what is happening in each moment, you will find this to be true.

You may have many other explanations for why you are struggling to focus: you’re tired; hungry; it’s too loud; it’s too quiet; you have too much to do; you’re not organised enough; or you’re not getting paid enough. These may all factor into why you do not feel motivated, and can be important to consider. But despite all these factors, the underlying mechanism when you are distracted is the same: you are too reactive to unimportant stimuli.

It’s important to understand and accept this mechanism of reacting to distractions. Otherwise, you may have some success in becoming more focused by changing your circumstances, but it will be more a process of trial and error than a meaningful and robust improvement in your ability to concentrate.

Let’s clarify this mechanism with a diagram and definition…

The distraction mechanism

You start your task (1) and you are trying to focus (stay on task) but you react to a stimulus (2) which is unrelated to your task. Once you follow the stimulus (3), you are spending time off task, and it has become a distraction. Soon (hopefully) you return to your task (4), but you have lost time. Other than the lost time, there is likely to be a further loss of productivity due to task switching.

On the other hand, when we focus, there’s an alternative mechanism at play…

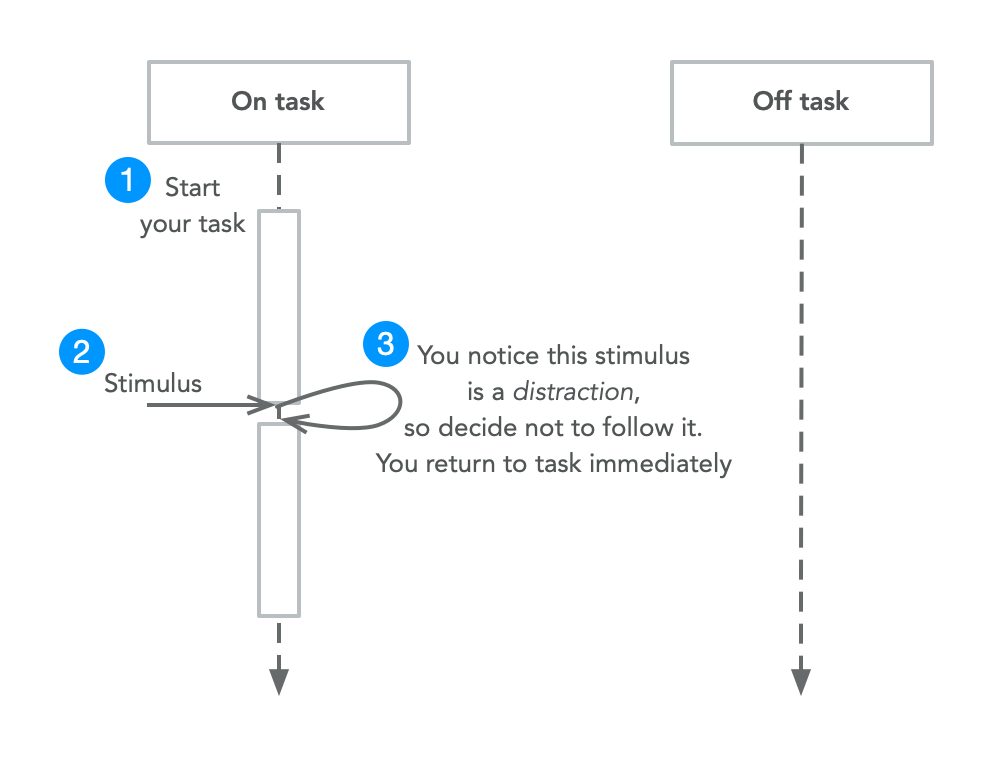

The focus mechanism

In this scenario, a stimulus appears which is unrelated to your task. However, you notice that the stimulus appeared and is unrelated to your task, and instead of following it, you let it go, and return immediately to your task. This only took a few moments, and since you did not fully switch tasks, you can immediately continue where you left off without extra effort.

By improving your ability to respond to stimuli as shown the second diagram, you will be better at focusing, whatever your circumstances.

This is possible with practice.

In fact, it is remarkably similar to the practice of meditation. In meditation, we typically try to maintain awareness of our breathing. We concentrate on the in-breath and on the out-breath. When thoughts arise, we recognise this but let them go. This is not always successful, but it’s a practice, and even a little regular practice can bring benefits (such as calming our anxieties).

When we focus on getting things done, it’s similar, but instead of concentrating on our breathing, we are concentrating on our tasks. This is also a practice: we will never be totally free of distractions, but we can still make serious improvements.

Exercise: Track Interruptions

Work on one of your tasks for a limited period of time. This should be no more than half an hour. Set an alarm to go off at the end of this period.

As you work, keep a sheet of paper and a pen by your side. Whenever a stimulus appears which demands your attention (and is not related to your task), leave a tally mark on your paper. (You can also write a short note about the interruption if it is something important that you do not want to forget). Now if possible, return to your task, without letting the stimulus become a distraction.

An interruption could be any number of things, and it could be external or internal:

- External interruptions come from your environment: this includes receiving message on your phone, new email coming in, any other notification from a device not related to your task, or someone you are with making small talk.

- Internal interruptions are when you interrupt yourself. Some thought arises in your mind which makes you want to do something other than your task. You may have an urge to check social media, to message someone, or to look something up. You may have a sudden desire to go and find a snack, or you may daydream about your next holiday.

Once your alarm goes off, add up your tally. It doesn’t matter so much how large this number is: your main aim is not to reduce interruptions, but to improve your awareness of them and train yourself not to react to them. Or rather, to react in a more productive way, which allows you to dismiss the interruption and immediately return to your task.

Please share your experience of this exercise in the comments!

The author’s experience

I tested this exercise myself whilst writing this, and had the sense that by trying to be aware of interruptions, I actually experienced fewer internal interruptions than I usually would. So the exercise helped me focus.

The How to Focus series

In this series of blog posts, we are learning how to focus. We’ll dive deeper into techniques you can use to practise and build your ability to focus, we’ll look at the role of your environment and your physical state on your concentration, and we’ll even question the concepts of productivity and focus. We’ll also have a special focus on technology, exploring how it can hinder and help us when we need to focus.

Whilst the series is mostly focused on productivity for work, study, or side projects, you should also find it helpful for those leisure activities which involve a little more effort, like reading or journalling.

In each post, we include at least one exercise to try, so that you can put what you learn into practice.

The next part of this series is now available: How to Focus – Part 2: Environment.

Very interesting, reminds me of some stuff in the ‘Indistractable’ book. My tallies were more than I expected🙈