“Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion”

The Righteous Mind is not a book about either mindfulness or technology (the topics of this website). It’s about morality and understanding others who may have a different sense of what is right and wrong. In the digital age, and particular over the last two years of the pandemic, so much of our lives have been online. With a tendency towards echo chambers in our online interactions, where we easily find views which confirm our own, it seems to me that we need to build our capacity to understand alternative views more than ever. That’s why, despite being slightly tangential to the topics of this website, I decided to review The Righteous Mind.

It’s worth noting however, that the author Jonathan Haidt does have things to say about our use of technology: he was interviewed for The Social Dilemma, and his most recent book, The Coddling of the American Mind, discusses the impact of smart phones and social media on teenagers who grew up with them. He’s concerned about the rise in anxiety in young people compared with previous generations, and their lack of tolerance for opposing views.

The Righteous Mind provides a framework which we can use to understand ideologies and the political spectrum. When we’re online, whether we’re reading an article by a journalist, the comments below that article, or opinions shared on a social media platform, there’s usually a moralistic stance behind the words we read or write. If we can understand more about how people form their views of what is right and wrong in the world, this can help us get along better with others, instead of judging people with opposing views to be extremists of some sort.

Part 1: Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

Haidt works with the metaphor that “The mind is divided, like a rider on an elephant, and the rider’s job is to serve the elephant.”.

Those who are familiar with Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, will recognise this divide as similar to the “system 1” and “system 2” thinking described in that book. However, in this book, the focus is squarely on moralistic thinking rather than a wider focus on cognitive biases in general. The two books are very much complementary.

Chapter 1: The Origin of Morality

The first chapter explains how views of morality are different in different cultures. People who are highly educated and liberal (as many academics are), tend to have different views from those in more traditional cultures. Haidt claims that this distorted the field of Moral Psychology for a long time, because academics were biased towards the kind of moral stance that they typically hold. Academics therefore came to the conclusion that morality is rationalist, meaning that children self-construct a sense of morality through reasoning, as they learn how to avoid causing harm through their actions.

Haidt makes the case against the rationalist theory by demonstrating that the moral reasoning people use to explain what is right and wrong is often invalid, and that they more often rely on kind of “gut feeling”. These intuitions comes partly from an innate sense of morality and are partly learned from the culture we grow up in.

Chapter 2: The Intuitive Dog and Its Rationalist Tail

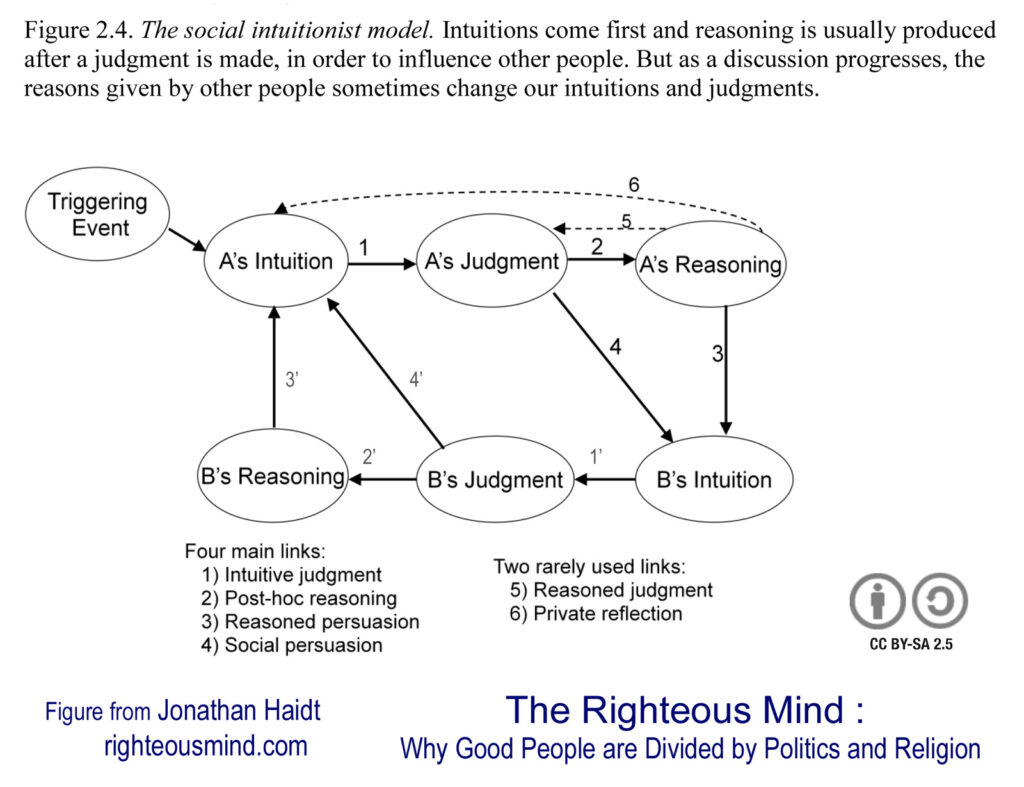

Haidt explores the relationship between moral intuitions and moral reasoning, and argues that moral intuitions are primary, and reasoning is used after-the-fact to explain our intuitions as convincingly as we can, whatever they may be. Under this “social intuitionalist model”, our reasoning alone rarely changes our own judgement (which came as intuition), though it is more likely to be changed when influenced by other people.

By now the metaphor of this part of the book is clear: intuition is the elephant and reasoning is the rider. Therefore, if we want to understand others and perhaps even change their minds, we can’t rely on rational arguments alone: we need to acknowledge and talk to their intuitive elephant. He says this theory is demonstrated by the advice given in Dale Carnegie’s classic book How to Make Friends and Influence People.

Chapter 3: Elephants Rule

Next Haidt expands on this theory by presenting several pieces of evidence for the idea that “intuitions come first”. Importantly, he defends intuition as necessary for us to get along, pointing out that psychopaths are essentially people who lack these intuitive feelings but have retain full capability for reasoning. Psychopaths can function in society, but are far more likely to commit serious crimes, so it’s a good thing that most of us have strong moral intuitions even if they are often flawed.

Chapter 4: Vote for Me (Here’s Why)

The book now moves on to present the evidence for the idea that “strategic reasoning comes second” after intuition. Haidt uses the analogy that our reasoning works more like a politician than a scientist: we are usually not searching for absolute truth but merely to justify our own intuitions and actions to defend our reputation. Our reasoning capability is likened to a press secretary: they always have to explain and defend actions, even when they don’t seem sensible. They have no power to change policy. Our reasoning capability almost always does this for our intuitions, it rarely changes what we believe.

Remarkably, there is evidence that those with higher IQs are no better at finding the objective truth, only better at constructing convincing arguments to defend their original belief. When we want to believe something we tend to ask “Can we believe it?” but when we are asked to believe something we don’t want to believe, we tend to ask “Must we believe it?”. Haidt makes that point that these days, that means we can believe almost anything we want to because we can always use Google to find evidence in support of our position (we will tend not to look for the contradicting evidence). Lastly, our intuitions often are formed not only in support of our individuals, but the group we are in (eg. political affiliation, football club we support, nation, etc).

Part 2: There’s More to Morality than Harm and Fairness

In this part, a new “central metaphor” is introduced: “The righteous mind is like a tongue with six taste receptors.”. This part of the book is very enlightening in allowing us to understand the moral beliefs of others. Where at first glance we may see their behaviour or beliefs as immoral, if we understand that their sense of morality is different, we can see that they are acting in line with their personal view of morality.

Chapter 5: Beyond WEIRD Morality

Here Haidt introduces the concept of WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) people having a different sense of morality than more traditional cultures. WEIRD morality is more individualistic viewing the world as separate objects, whereas traditional cultures tend to be more “sociocentric”, focused on relationships and groups. The WEIRD morality tends to focus mostly on the values of harm and fairness, and tends to be associated with liberal political beliefs.

Haidt explains that he saw this difference first-hand when he did research in India. As a young man with liberal beliefs, he found it easier to understand American conservatives after returning from his time living in India. By then he could understand, both theoretically and through personal experience, that people can have different moral matrixes. He could finally see that conservatives were not immoral, they just had a different sense of morality to liberals. He claims that WEIRD morality is narrow, whereas other moralities tend to be broader, having additional concerns such as “divinity”.

Chapter 6: Taste Buds of the Righteous Mind

This core chapter of the book introduces “moral foundation theory”, the idea that morality is like taste, in that we have a number of “receptors” for which different people can have different preferences. Haidt suggests five candidates: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. For example for the authority/subversion foundation, some people believe it is important to establish a hierarchical system where we follow our superiors, whilst others try to flatten organisational structures and have a disregard for authority.

Chapter 7: The Moral Foundations of Politics

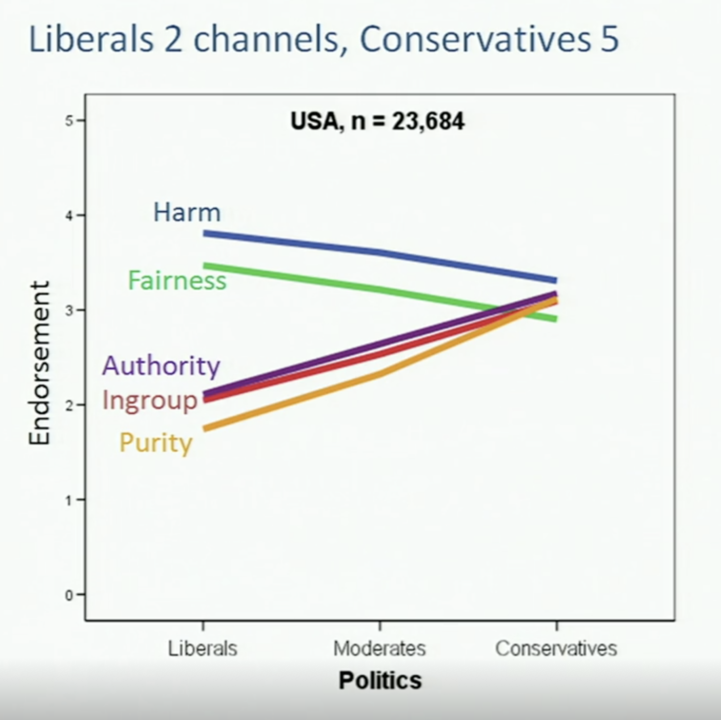

Haidt now explains each of the moral foundations in more depth, and makes the case that liberals care most about care & fairness, whereas conservatives also care about loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

Chapter 8: The Conservative Advantage

Haidt claims that conservatives (at least in the American context of the US Republican Party) understand the social intuitionist model better (they speak more to our elephant, our intuitions) and they also touch each moral receptor from the moral foundations theory. This helps to explain why the Republican Party performs well in poorer rural areas, which, rationally, would benefit from the redistribution policies of the Democratic Party.

Haidt also explains an alteration to moral foundations theory, the adding of an additional liberty/oppression foundation.He also clarified the fairness/cheating foundation based on the feedback from both conservatives and liberals who claimed they believe in fairness whilst the other side does not. Both believe in fairness, but the focus of fairness differs: liberals tend to believe in equality whereas conservatives tend to believe in proportionality (people should receive what they’ve worked for, even if that means some people will be poor). The fairness foundation was redefined to focus purely on proportionality, because the liberal concept of fairness as equality was captured by the care and liberty foundations.

Part 3: Morality Binds and Blinds

The final part of the book uses the metaphor that “We Are 90 Percent Chimp and 10 Percent Bee.”. It attempts to explain our tribalism, particularly in politics, which binds us closer together but blinds us from understanding the views of other tribes.

Chapter 9: Why Are We So Groupish?

Haidt discusses the concept of group selection: natural selection at the level of the group, rather than the individual. This theory was discounted in much of the late 20th century, but has been revived by new evidence more recently, which Haidt presents here. He argues that human nature is mostly selfish (competing with other individuals to pass on their genes) but partly “groupish” (supporting the group we are in to pass on their genes). It’s worth noting that group selection seems to still be controversial (eg. Richard Dawkins still does not accept it) but, it seems to me that the distinction is not essential for the following chapters: the fact that humans for whatever reason, tend to act groupishly seems reasonable without having the agree on the evolutionary mechanism for this quality.

Chapter 10: The Hive Switch

This chapter discusses the idea that under certain conditions, we act in the interest of the hive (group) rather than the individual. We are 10 percent bee. Haidt describes three common ways to switch us into hive mode: experiencing awe in nature, certain kinds of drugs (hallucinogens), and raves (communal dancing). He explains some of the biological mechanisms that may power the hive switch: the hormone oxytocin, and mirror neurones.

Chapter 11: Religion is a Team Sport

Haidt discusses religion and explains how “New Atheist” criticisms of religion fail to recognise a core aspect of religion. By focusing on the scientific truth of beliefs and how invalid beliefs can inspire actions that may be harmful (eg. terrorist attacks), the New Atheist approach misses the importance of belonging in religions. Haidt argues that a sense of belonging to a group is at the core of religion, and it allows a community to be established with a shared sense of morality that can be advantageous to all: eg. ultra-Orthodox Jews have dominated the diamond industry because their religious community ensured high levels of trust which keeps transaction costs low.

Chapter 12: Can’t We All Disagree More Constructively?

The book finishes by focusing most on the political divide between liberals and conservatives (the book recognises that there is a wider range of political views, but that it’s easiest to use the liberal-conservative spectrum as it’s the most commonly discussed with the most data). Haidt explains that there are biological factors that can predispose us to a particular political ideology. Those who are attracted to novelty, variety and diversity have a predisposition to liberal politics. Those who prefer to stick to what they know, and are more sensitive to signs of threat, have a predisposition towards conservatism. Haidt suggests that it is more difficult for liberals to understand conservatives than the other way around, because both liberals and conservatives see care and fairness as a part of morality, but only conservatives see loyalty, authority, and sanctity as an important part of morality. Haidt also suggests that having people of such different views is a feature, not a bug, of our society. Liberals push us to care for every member of society, and address injustices, whilst conservatives ensure that any societal changes are gradual enough to not destroy the structures that keep society cohesive and productive. Haidt also credits libertarians with ensuring that we have free markets which keep prices down, raising the quality of life for all. Finally, Haidt suggests to bring about a more civil politics in America, we need to create the conditions whereby politicians can form friendships with those who have opposing views, as he claims they used to more frequently when it was more common for politicians to live in Washington DC rather than their home state.

Key takeaways

In the conclusion, Haidt suggests we take away three main lessons from the book. Below, I summarise these and comment on how they are relevant in the context of online discourse.

The first takeaway is the awareness that people (ourselves and others) are ruled more by intuitions than rational thought. In the online context, it’s worth remembering this before we go about trying to disprove other commenters through rational arguments. It’s next to impossible to change another’s views unless you can connect on a more human level to understand where their views are coming from, and to do that sincerely, you need to be open to the possibility that your own view may be changed by the other person. Personally, I’ll try to reserve discussions of this kind for a more personable, offline environment.

The second takeaway is that we should be suspicious of “moral monists” – people who claim there is only one true type of morality for all. This seems clear if we look at the evidence and listen to others, and it’s worth reminding ourselves, particularly when we’re looking at online comments, that others may place a different priority on what is right and wrong than we do. Without recalling this insight, it’s easy to make the mistake of thinking that others are not in accordance with morality, when in fact they may just have a different sense of morality.

The final takeaway is that we have a “hive switch”, that when triggered makes us prioritise our group over ourselves. This seems to me a mixed message: as well as bringing a sense of belonging which improves our wellbeing, it can drive people to act altruistically, which leads to better lives for all of us (or at least our group), but it can also lead to hostility or lack of concern for those outside of our group. Through online communities, we can connect with people with shared interests from all around the world to an extent that would have been unimaginable in previous generations, however, we can also get drawn into echo chambers, where we are rarely exposed to alternate views. Sometimes, our tendency to seek out those with similar views is enhanced by personalisation algorithms, which deepens this groupish tendency. With this in mind, it may be healthier to consciously reserve our hive switch for offline contexts, such as when we walk in nature or dance together.

YourMorals.org

Throughout the book, Haidt mentions yourmorals.org, a survey website on morality topics, on which some of Haidt’s research is based. I decided to try it out myself to learn about my own moral matrix. After completing surveys on the site, you can explore how you compare to others. However, I found it wasn’t so easy to interpret the results. For example, I found that I tended to have less strong scores for every moral foundation compared to the average, so this made it more difficult to determine which foundations were more important to me that others. I also found the site to be buggy is some places, for example the most prominent results diagram didn’t match up to my score shown when using the comparison tool.

I also found that the differences between different groups such as liberals and conservatives (or religious and non-religious) seemed far smaller than the diagrams suggested in the book. It was clear that differences exist, but it seems to be slight differences in priority rather than suggesting that liberals and conservatives are completely different species. Perhaps this should give us hope that we can find shared understanding!

Conclusion

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book and could barely put it down. As Jonathon Haidt often points out, his theories are quite new in the grand scheme of things, and sometimes controversial. On that basis, we shouldn’t read this book as an absolute and accepted truth. But even if the theories are not 100% correct, they can still be helpful, in that same way that Issac Newton’s theories of gravity and mechanics from the 17th century are still be very helpful today (though we now know they do not apply in every context).

The Righteous Mind helps us to understand others with different views, and helps us to understand why we often struggle to understand different views. In the digital age of echo chambers, personalisation algorithms, bots, and a fragmented media, anything that can help us understand others and our cognitive biases concerning others, is indeed useful.